U.S. Supreme Court Expands Ministerial Exception to Bar Employment Claims Against Religious Institutions

Reposted from the Labor & Employment Law Navigator Blog – Click Here to Subscribe

In a 7-2 decision this week, the United States Supreme Court clarified and expanded upon its 2012 decision in Hosanna Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. EEOC, 565 U. S. 17, by holding that the First Amendment’s religion clauses prevent civil, secular courts from adjudicating employment-related claims brought by teachers and others entrusted with carrying out an organization’s religious mission and goals.

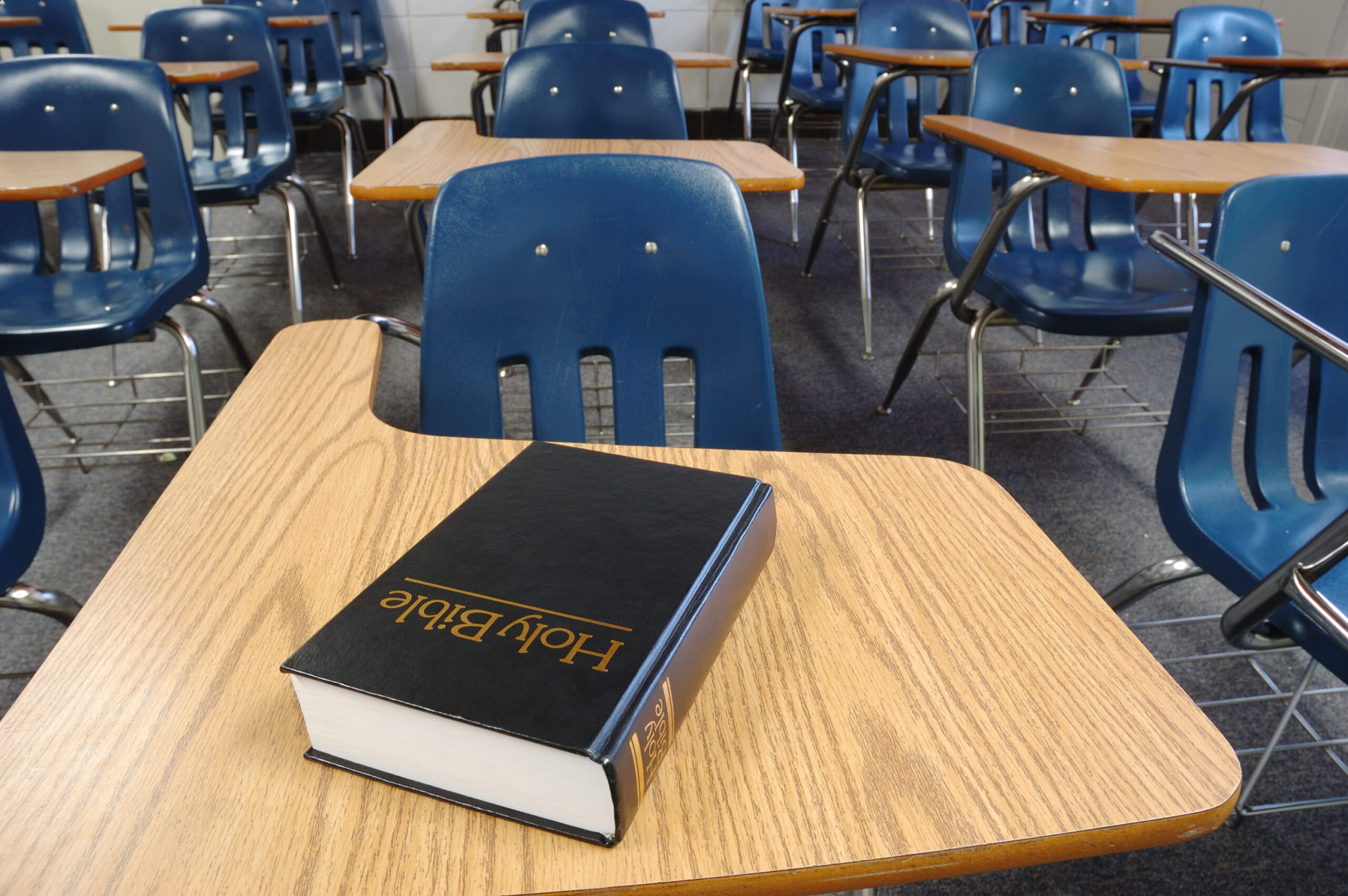

Under the First Amendment, religious institutions may “decide for themselves, free from state interference, matters of church government as well as those of faith and doctrine.” Kedroff v. Saint Nicholas Cathedral of Russian Orthodox Church in North America, 344 U. S. 94, 116. Applying this principle, the United States Supreme Court held eight years ago in Hosanna that the First Amendment barred a court from hearing an employment discrimination claim brought by a teacher, Cheryl Perich, against the religious elementary school where she taught. Adopting a “ministerial exception” to laws governing the employment relationship between a religious institution and certain employees, the Court found relevant in Hosanna that Perich held the title “Minister of Religion, Commissioned,” that she had religious educational training, and that she had responsibility to teach religion and participate with students in religious activities.

Plaintiffs in the Court’s decision this week, Agnes Morrissey-Berru and Kristen Biel, were elementary school teachers at Roman Catholic schools in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, California. Each of their employment agreements set out the schools’ mission to develop and promote a Catholic School faith community and also imposed commitments regarding religious instruction, worship, and personal modeling of the Roman Catholic faith. Each was required to comply with her school’s faculty handbook, which set out similar expectations. Each taught religion in the classroom, worshipped with her students, prayed with her students, and had her performance measured on religious bases.

Both teachers sued after their employment was terminated and both cases were dismissed by California district courts on summary judgment. Applying only the four factors outlined in the Hossana decision, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the dismissals based on the fact that the teachers did not have the formal title of “minister,” lacked or had limited formal religious training, did not hold themselves out publicly as religious leaders, and did not have a ministerial background.

This week, however, Justice Alito writing for the majority, noted that the Court in Hossana declined to adopt a “rigid formula” for determining whether the ministerial exception applies, and instead noted that the exception may vary from case to case. “What matters, at bottom,” according to the Court, “is what an employee does.” In the cases of Biel and Morrissey-Berru, the Court held that ministerial exception applied because there was “abundant” evidence that the teachers “performed vital religious duties,” which in their cases included an obligation to teach students about the Catholic faith, as outlined in their employee handbook, as well as carrying out the school’s religious mission, praying with students, and attending Mass with them. The fact that their schools expressly saw them as playing a vital role in carrying out the Church’s mission was important in the Court’s analysis.

In clarifying and broadening the standard to whether an employee “carries out a religious organization’s mission and goals” and/or “performs vital religious duties,” the Court has arguably opened the door for interpretation and application of the ministerial exception beyond religious schools and their teachers and ministers. Religiously-affiliated employers now have the ability to apply the exception regardless of whether an employee is a “minister,” or an educator, or whether (as the Court hints in its slip opinion) the employee is even a “practicing” member of the religion with which the employer is associated. If furthering religion is a critical part of the employee’s job and if the employer has a good-faith basis that the position involves carrying out, fulfilling, or communicating the faith in some way, the Court’s decision this week provides a plausible basis for applying the ministerial exception.

It is important to note that the Court’s decision in Our Lady of Guadeloupe School does not mean religious employers should scrap their anti-discrimination policies or categorically apply the exception to their entire workforces. It does, however, provide religious institutions greater control over deciding who teaches, ministers, and delivers their religious message and to make employment-related changes.